Some years later, the two artists involved, Mireia C Saladrigues and Verónica Aguilera, confirmed to me what I’d experienced: “We wanted to find out if we could get people to look at industrialised fishing from a different perspective”.

Their intervention, which they was named Fiskemennesket-Menneskenfisket, was not about telling people to think differently about fish. Rather, they looked for ways to enable encounters and conversations from which such an understanding might flow of its own accord.

And that’s why, having first spent time with former fishermen, they ended up on Bornholm’s high street, dressed as fishermen, handing out beautifully wrapped herring that they’d salted themselves. They even designed and printed the wrapping paper specially for the occasion.

People don’t change because you tell them to, or when they’re exposed to shocking stories and images – the tactics used by the environmental movement over decades. Change happens – or so I concluded on on Bornholm – when people share meaningful experiences in rich, real-world, contexts.

Eleven years after that Bornholm moment, a book was finally published that celebrated the kind of art that had so moved me then.

Playing For Time: Making Art as if The World Mattered brings together the thinking and real-world practices of 64 artists, writers and curators.

“Reconnection with nature is not a moment of magic” the book’s author Lucy Neal, explains; “it’s more of a life practice – dedicated acts of imagination, creative thought, and actions, that persist through time”. The intention of the book (which was co-edited with Charlotte Du Cann) is to create conditions for more of these experiences to happen, more widely, and on a continuous basis.

This intention has never felt more important than it does now – and is one reason why the book deserves our attention more, today, than when it was published.

Few of the ‘acts of imagination’ described in Playing For Time take place in art galleries, or museums.

On the contrary: they tend to involve cooking, writing, caring, growing, making, building, or teaching – for the most part, in real-world situations.

There’s not much staring at venerated artefacts involved – but quite a lot of listening, connecting, sharing and supporting.

Social Fermentation

Two examples from the hundred or more that fill the book:

In Finland, Eva Bakkeslett gives workshops on baking, and on the art and culture of viili, or Finnish live yogurt. (She cultivates yoghurt using Eastern European roots, and bakes bread with old microbial cultures from Russia).

“Humans are part of nature, linked to a network of bacteria” the artist explains. “My workshops are about working with nature instead of fighting it. Together we co-create new cultures that embody collaboration”.

Bakkeslett describes her practice as ‘social fermentation’ – a process that gains its vitality from the sensuous pleasures to be had from making, eating, and sharing fermented foods with others

A second example, this time in England, also involves food.

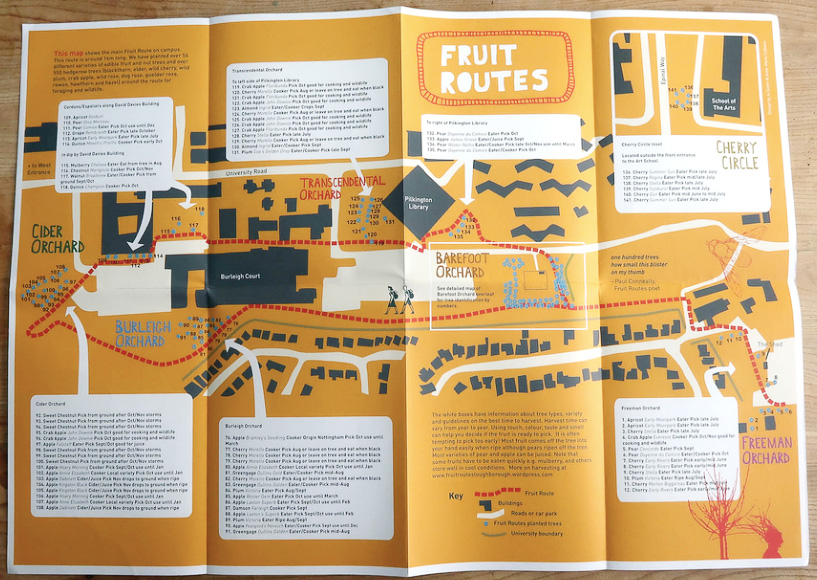

At Loughborough University, the artists Jo Salter and Anne-Marie Culhane worked with the university’s sustainability faculty during the planting of 150 fruit and nut trees right across the campus.

A large folding map (above) shows all the edible trees planted as well as other forageable plants on what they named the Fruit Route. https://josalter.org.uk/portfolio/fruit-routes-maps

“These collaborative arts practices carry seeds of the future that can take root and grow” writes Lucy Neal – “but the philosophy of the book is to make it happen yourself”….

Playing For Time, edited by Lucy Neal, is available from Oberon Books. https://www.oberonbooks.com/playing-for-time.html